Life as Invitation II: A Philosophy of the Bench

I'm learning that the most important work I do as a therapist has nothing to do with insights or interventions. It happens in the pauses—the moments between my question and a client's response, the silence after something difficult is named, the space we create together just by sitting with what is.

I've learned this from one client in a particularly evocative way. As with many students who come to see me, she didn't come for a particular reason. She had—and continues to have—a thriving university career: engaging classes, meaningful friendships, a packed social calendar. But something simply wasn't working. Over time, we developed a number of approaches and strategies that help keep everything going. At one point she described this work as keeping all the various train cars in her life moving safely—making sure there isn't a derailment! Her most effective habit is something she came up with herself. Even on the busiest days, she takes a few minutes to sit on a bench on campus before moving on to the next activity on her very full calendar.

Over many sessions, we find ourselves returning to this image of the bench again and again. What began as a simple habit has turned into what I've come to call the philosophy of the bench. Nothing much happens during these few moments on the bench. Just sitting and watching the world go by. And this is the point. It is almost as if she is catching up with herself, and in doing so she can shift from managing her life to actually meeting it.

And this way of being in the world has taught me something important about therapy itself. We spend much of our time trying to decide major life decisions: Should I move to a new city? What field do I want to work in? Do I want to change jobs? But those decisions are in the future, and when the time comes, we use criteria we often don't even understand.

On the other hand, we have invitations to choose moment after moment: How do we want to show up for what is happening right now? Whether or not we realize it, we are making these choices all the time.

The pioneering psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl spent his life pondering the most significant choices people can make. He famously said, "Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose a response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom." As Frankl makes clear, this space does not need to be a large one. It can be found in an extra breath before we speak, a moment of grounding before a therapy session—or a few minutes spent on a bench.

As important as these moments are, they're often lost in the continuous cacophony of everything we need to do. And in response, we dream of getting away—vacations, idyllic retreat centres, anywhere but here. The "geographic cure" is wonderful, of course. The problem is that we always need to come back.

The philosophy of the bench suggests something different: that we can meet all the things we have to do from our whole, grounded self. We can face what Buddhism sometimes calls "the 10,000 things"—all the demands, decisions, and daily tasks of our lives—not by running toward them frantically, but by letting them come to us while we remain centered.

The 13th-century Zen teacher Dōgen Zenji taught: "If we go and meet the 10,000 things, this is illusion. If you let the 10,000 things come to you, this is enlightenment."

This is what I mean by living a life of invitation. Not grand gestures or dramatic retreats, but small spaces woven into the ordinary rhythm of our days—a bench, a breath, a moment of stillness before moving forward. These spaces allow us to receive the invitations life is constantly extending: to show up fully, to choose our response, to trust that we don't have to chase everything down.

In my therapy practice, I've seen how these small practices transform everything. Not because they solve problems or answer big questions, but because they change our relationship to the problems and questions themselves. We stop meeting life with urgency and start meeting it with presence.

So this week, I'm wondering: What form does your bench take? As we move towards the holidays, might it be time to begin such a habit? What small space could you carve out—not to escape the 10,000 things, but to meet them from your whole self?

Three Invitations:

Forward this newsletter to someone who might be interested in these questions about contemplation, therapy, and living with intention.

Book a free consultation if you're an emerging adult (17-30) navigating transitions and looking for therapy that honors your whole self. I offer experiential therapy both in-person in Toronto and online across Ontario. Most university students are fully covered through direct billing to student insurance—no upfront cost, no paperwork. For those without coverage, sessions are $120.

Subscribe - if you are not already - to receive these weekly reflections every Thursday.

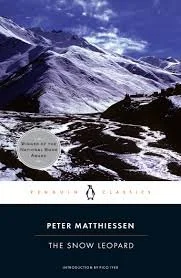

Book Recommendation: The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen

If a few minutes on a bench can powerfully affect our perspective and our ability to face our life challenges, it can be educative—and deeply enjoyable—to soak up the words of someone who dedicated his entire life to observation in multiple forms: as a naturalist, a Zen Buddhist, and as a longtime writer and editor.

Peter Matthiessen packed a lot of life into his 86 years. His 1978 book The Snow Leopard, the National Book Award winner, is a masterclass in observation. On the surface, The Snow Leopard is about an adventure Matthiessen took with his friend George Schaller to the mountains of Tibet in search of the mythical snow leopard. But what I love most about the book is the way Matthiessen can seamlessly shift perspective. At one point he writes as a careful and precise scientist describing "the pale lavender-blue winged blossoms of the orchid tree (Bauhinia)," and in the next he describes the heartbreak of the death of his wife the year before and the pain of leaving his young son at home. Adding to the rich and complex mosaic, Matthiessen spends pages describing the complex cosmology of Tibetan Buddhism. Throughout the book he shifts deftly between these—not only different types of content—but radically different ways of seeing the world.

In the introduction to my Penguin Classics edition, Pico Iyer (no stranger to past issues of this newsletter) agrees that The Snow Leopard "offers a kind of handbook into how precision and attention work, and how language, at its very best, disappears inside the very thing it describes." As well as being a traditional adventure story, The Snow Leopard is a beautiful example of what is possible when one dedicates a lifetime to training perception itself.